Kon Trubkovich: Ophelia Tennis Elbow 134

-

Works

-

Kon Trubkovichcakewalk, 2024Oil on linen20 x 16 in (50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Kon Trubkovichcakewalk, 2024Oil on linen20 x 16 in (50.8 x 40.6 cm) -

Kon TrubkovichDance before my mirror, 2024Oil on linen20 x 16 in (50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Kon TrubkovichDance before my mirror, 2024Oil on linen20 x 16 in (50.8 x 40.6 cm) -

Kon Trubkovichoff to the nunnery, 2024Oil on linen20 x 16 in (50.8 x 40.6 cm)

Kon Trubkovichoff to the nunnery, 2024Oil on linen20 x 16 in (50.8 x 40.6 cm) -

Kon TrubkovichRavine, 2024Oil on linen81 x 48 in (205.7 x 121.9 cm)

Kon TrubkovichRavine, 2024Oil on linen81 x 48 in (205.7 x 121.9 cm) -

Kon TrubkovichSatellite, 2024Oil on linen20 x 24 in (50.8 x 61 cm)

Kon TrubkovichSatellite, 2024Oil on linen20 x 24 in (50.8 x 61 cm) -

Kon Trubkovichspitting image, 2024Oil on linen48 x 35 in (121.9 x 88.9 cm)

Kon Trubkovichspitting image, 2024Oil on linen48 x 35 in (121.9 x 88.9 cm) -

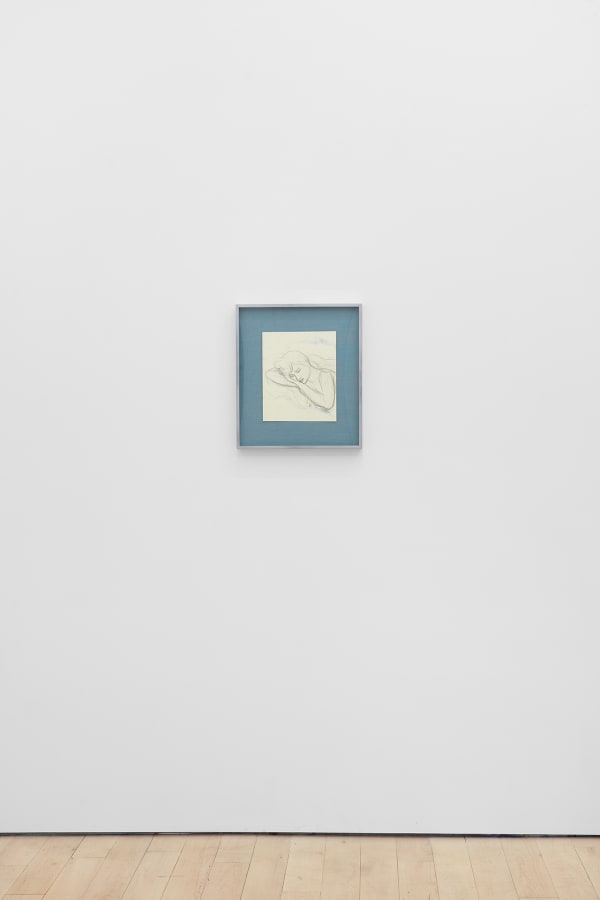

Kon TrubkovichUntitled, 2024Graphite and colored pencil on paper10.5 x 8.5 in (26.7 x 21.6 cm)

Kon TrubkovichUntitled, 2024Graphite and colored pencil on paper10.5 x 8.5 in (26.7 x 21.6 cm)

Framed 17 x 15 in (43.2 x 38.1 cm)

-

-

Text

We all know about pixelation. But what about its old, forgotten cousin—pixilation, which describes not a pictorial state but a mental one? Despite only differing by a single letter, the two words have different roots.Yet pixilated has an oddly similar meaning—“mildly insane, bewildered, confused”—to the scattered, streaky and confused look of pixelated digital images.

One can’t help but dwell on the kinship of these two fuzzy states when contemplating the work of the NewYork painter KonTrubkovich, who has been long fascinated with “the pause”—that meta-state of mind and tech where we (or the VCR) are stuck on hold, temporarily being in the process of doing.

His fascination was seeded unconsciously in the late 1980s, when he was an artistic boy of 10 and his family was still living in the Soviet Union and his grandfather brought back a VCR as a gift from a trip abroad. “It was a rarity then,” recalls Trubkovich. “My friends used to come over and watch American movies.”

A year later,Trubkovich and his family fled the tumult of the USSR disintegrating and landed in the U.S., and he spent his 1990s growing up in Philadelphia and New York during the VCR’s heyday. But it wasn’t until 2005, when he was living on his own in NewYork and trying to build a life as a painter, that the poetry of the pause hit him. He had taken a cross-country trip the year before and documented it with a Hi8 video camera. While reviewing the footage, he found himself repeatedly pausing moments to look at, and it struck him that the images’ lo-fi quality was not a drawback, it was an asset.Yes, photographs on film are neat and sharp—but thoughts and memories and even truths are not.They’re blurry, unstable, scattered.

“They had this intense, layered narrative quality that I responded to,” says Trubkovich. “The streaks and shifts and static added a quality that reminded me of the gestures of abstract expressionism. Not many people would look at a paused video screen and think it was painterly, but that is what I saw.”

And that’s what he did. Over the next decade, Trubkovich became known for pixelated paintings of socio-political figures in turmoil; so realistic are his pauses that some mistake them for photos or screen grabs.The effect adds levels of both soothing low-tech nostalgia and disturbing low fidelity to the scenes he presents. Did that really happen like that? What’s the truth? Undergirding this jittery sensibility are the violent seismic shifts Trubkovich lived through with the end of the Soviet Union and the geopolitical theater he has viewed, via video, ever since.

His paintings have tried and failed to make sense of all his memories and all the stories—as do all accounts of such apocalypses. (That said, his simple paused portraits of an angry President Ronald Reagan do convey an awful lot.) Now, on the with another catastrophe looming with the the 2024 U.S. Presidential Election,Trubkovich has taken a surprisingly escapist tack with a series of paintings that summon up not Baroque figures fighting but Pre-Raphaelite heroines and flowers. The show is titled Ophelia, after Hamlet’s innocent but unstable inamorata that he tragically puts on pause. And despite the lovely faces and colors on display, there is a haunting quality to the paintings, as though the flowers are a layer of funereal remembrance placed over the images underneath, recalling Millais’ famous painting of a drowning Ophelia covered in flowers.

“This show was my way of taking a break from my thoughts that are so based in my own politics and migration and the world around me,” explains the artist, who lives in Brooklyn with his wife Alexandra Butler, a writer and therapist, and their two children. “I wanted to make work rooted in exploring something universal, beautiful, even pleasureful.”

Of course, there are those who might question the dying Ophelia as a reference that brings pleasure, butTrubkovich’s works are about memorializing the past, too.There may be as much value in romanticizing the clamorous past as in raking it up. We all need some peace sometimes, even if it’s just a pause in the fighting.

David Colman

-

Installation Views